Handling bare dies has always been the most stressful part of the semiconductor backend process. You spend weeks processing a wafer, grinding it down to the thickness of a human hair, and dicing it into thousands of tiny chips. Then, you have to ship it.

This is where the nightmare of logistics begins. Traditional pockets and trays often fail when dealing with ultra-thin or fragile compound semiconductors. The solution that has gained traction in international fabs is the vacuum release box.

Unlike standard waffle packs that rely on physical pockets to contain a die, these specialized containers use surface tension and vacuum physics to hold components securely. Companies like Hiner-pack have recognized that as chips get smaller and more brittle, the packaging must evolve from a simple container to a precision tool.

Here is a look at why this technology is becoming the standard for high-value die transport.

Understanding the Mechanics of a Vacuum Release Box

To understand the value, you have to understand the mechanism. A standard chip tray allows the component to move slightly. Even with a cover tape or a clip, there is a gap. For a robust silicon chip, this is fine. For a brittle Gallium Arsenide (GaAs) or Indium Phosphide (InP) die, that movement causes micro-fractures.

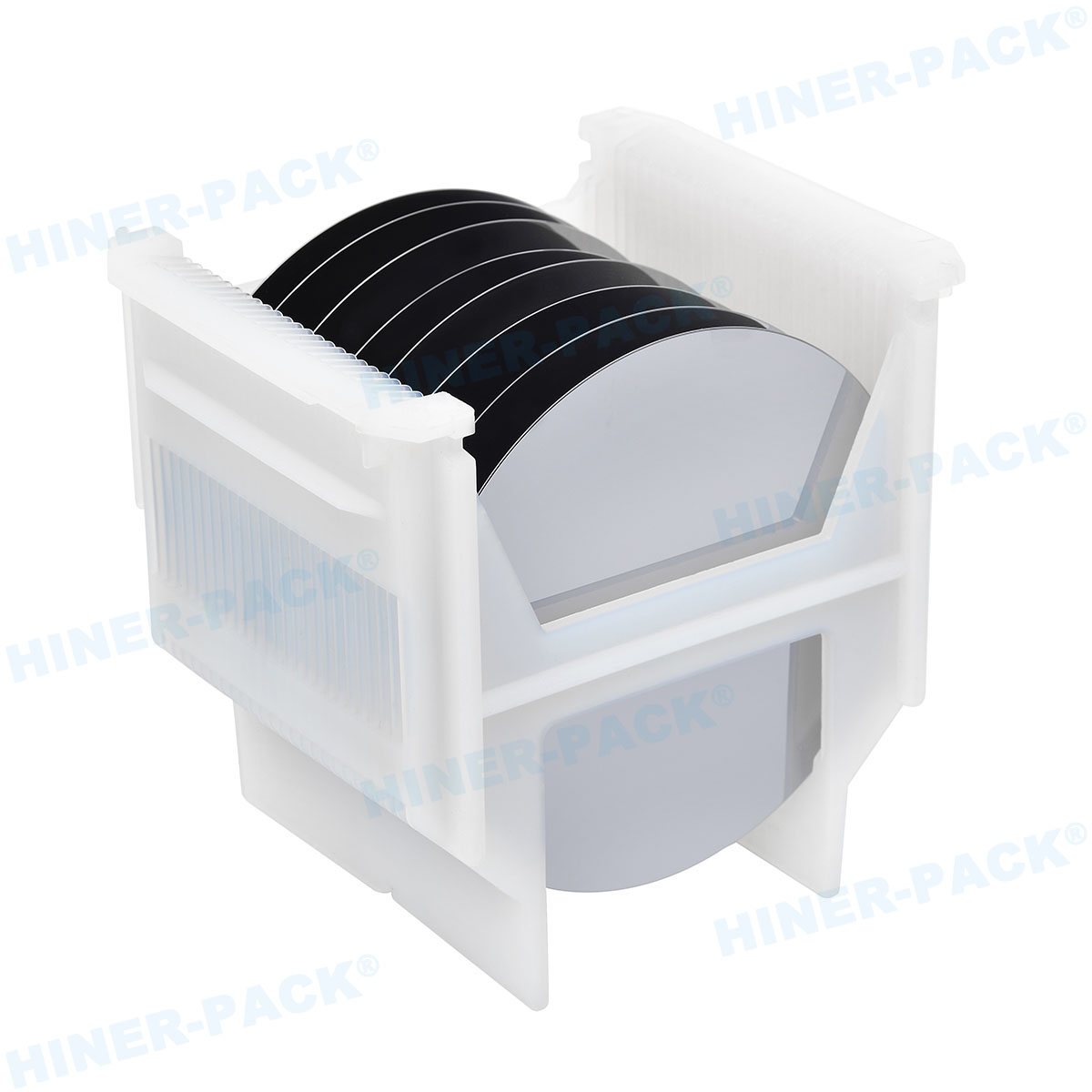

The vacuum release box works differently. It consists of a carrier tray with a specialized flexible membrane stretched over a mesh bottom.

The dies are placed directly onto this membrane. The tackiness of the gel holds the dies firmly in place during shipping. They do not rattle. They do not touch each other. They are suspended in place.

When it is time to remove the die, you don't pry it off. You place the tray on a vacuum chuck. The vacuum draws air through the bottom mesh, pulling the membrane down. This reduces the surface area contact between the die and the gel by over 90%. The die effectively "floats," allowing a vacuum collet to pick it up with zero resistance.

eliminating Edge Damage During Transport

The primary enemy of yield in chip logistics is edge chipping. In a standard pocket carrier, the die edges hit the plastic walls of the pocket whenever the package is jostled.

With a vacuum release box, there are no sidewalls impacting the die. The die is immobilized by the bottom surface.

This is critical for photonics and optoelectronics. These components often have active facets on the edge of the chip. If the edge hits the side of a plastic tray, the device is ruined. By securing the die from the bottom, you preserve the pristine condition of the edges.

Handling Ultra-Thin and Back-Ground Wafers

Semiconductor trends are moving toward thinner profiles. We are seeing wafers ground down to 50 microns or less for stacked die applications.

At this thickness, silicon acts more like foil than stone. It curls and cracks under the slightest stress. You cannot put a 50-micron die in a waffle pack; it will slide out of the pocket or crack when the lid is closed.

The vacuum release box provides a flat, rigid support structure. The membrane conforms to the die’s backside topography, offering full support. This prevents the warping that leads to cracks.

The Importance of Mesh Count Selection

Not all release boxes are the same. One of the key specifications engineers must look at is the mesh count. This refers to the density of the grid supporting the membrane.

For very small dies (under 1mm square), you need a high mesh count. If the mesh is too coarse, the small die might tilt into the holes of the grid, causing issues during the pick-and-place process.

For larger dies, a lower mesh count is often preferred to allow for a stronger vacuum pull-down effect. Suppliers like Hiner-pack often assist engineers in matching the specific mesh count to the die dimensions to ensure the release mechanism works smoothly without tilting the component.

Variable Retention Levels for Different Materials

Adhesion is not one-size-fits-all. A heavy IGBT power module needs strong adhesion to stay put. A tiny MEMS mirror needs very light adhesion, or it might be damaged during the release.

The vacuum release box comes in distinct retention levels—typically categorized as Low, Medium, High, and Extra High.

Choosing the wrong retention level is a common error. If the tack is too high for a small, fragile part, the vacuum might not be enough to break the bond, leading to a "pick failure" where the machine nozzle misses the part.

Conversely, if the retention is too low for a heavy part, the dies might shift during air transit. It requires a balance between the mass of the die and the surface area in contact with the gel.

Solving the "Sticky Residue" Fear

A common hesitation engineers have regarding gel-based carriers is residue. Will the gel leave a mark on the backside of the die? In wire bonding or eutectic die attach processes, backside contamination is a showstopper.

High-quality modern boxes use cross-linked silicone or non-silicone elastomers that are designed to be "residue-free." The chemistry is stable.

However, storage conditions matter. If a vacuum release box is stored in high heat for months, the material properties can change. This is why trusted supply chains monitor the shelf life of these boxes carefully.

Hiner-pack and the Consistency of Gel Flatness

In the automated assembly line, consistency is everything. The robotic arm moves to a specific Z-height coordinate. If the gel surface in the box is wavy or uneven, the vacuum nozzle might crash into the die or fail to seal.

Manufacturing these boxes requires precise control over the membrane tension. This is an area where Hiner-pack has focused its production capabilities. By ensuring that the membrane remains perfectly flat across the entire working area of the tray, they minimize machine errors at the customer’s site.

Inconsistent tension in cheaper alternatives often leads to the "trampoline effect," where the die bounces slightly when the vacuum is applied, causing alignment errors.

ESD Control in Gel-Based Carriers

Static electricity is the silent killer of chips. You might think that a rubbery gel membrane would be an insulator and a static generator.

However, professional-grade boxes are engineered with ESD (Electrostatic Discharge) properties. The plastic frame is conductive or static-dissipative. More importantly, the membrane itself is often doped with conductive materials or engineered to provide a ground path.

When the tray is placed on the metal vacuum chuck of the unloader, the static charge is safely drained away from the die. This is non-negotiable for CMOS image sensors and other static-sensitive devices.

The Pick-and-Place Workflow Integration

Switching to a vacuum release box does require a change in equipment. You cannot use a standard waffle pack feeder.

The pick-and-place machine must be equipped with a vacuum stage (often called a "stage up" or "ejector" module). The machine sequence is:

The tray moves into position.The vacuum is activated under the specific pocket or the whole tray.The camera confirms the die position.The top nozzle picks the die.

While this adds a step to the machine setup, the increase in yield usually pays for the tooling change within a few weeks. The reduction in dropped dies and cracked parts is immediate.

Logistics and Reusability

From a procurement standpoint, these boxes are more expensive than simple plastic trays. However, they are often reusable, depending on the cleanliness requirements of the fab.

For internal transfer between two cleanrooms, a facility might reuse the boxes dozens of times. For shipping to an external customer, they are typically treated as single-use consumables to guarantee purity.

The latching mechanism and the hinge durability become important here. A broken latch during shipping renders the protection useless. The external shell must be rugged enough to survive the drop tests required by international shipping standards.

Final Thoughts on Advanced Die Packaging

The semiconductor industry is unforgiving. As we push the limits of physics with thinner wafers and more complex compound materials, the margin for error in logistics vanishes.

The vacuum release box is no longer a niche product for exotic labs. It is a necessary component of the high-volume supply chain. It bridges the gap between wafer processing and final assembly, ensuring that the value you added to the silicon is not lost in a FedEx truck.

Whether you are sourcing from major global distributors or specialized manufacturers like Hiner-pack, the key is to understand your die physics. Match the mesh, the retention level, and the box size to your specific application. Your yield depends on it.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: How do I select the correct retention level for a vacuum release box?

A1: Selection depends on the die size, weight, and backside roughness. Generally, smaller and lighter dies require lower retention levels (Low or Extra Low) because they have less mass to hold them down during release. Large, heavy dies require High retention to prevent shifting during shipping. Smooth, polished backsides adhere more strongly than rough-ground backsides, so you may need a lower retention level for polished dies to ensure easy release.

Q2: Can a vacuum release box be cleaned and reused?

A2: In many cases, yes. If the gel membrane is not physically damaged or punctured, it can be cleaned using integrated sticky tape or specialized cleaning rollers to remove dust and particles. However, you should not use solvents or alcohol on the membrane unless the manufacturer specifically states it is safe, as this can degrade the tackiness.

Q3: What happens if I use the wrong mesh count?

A3: If you use a mesh count that is too low (coarse) for a very small die, the die may tilt or settle into the valleys of the mesh pattern. This causes the die to sit at an angle, leading to pick-up errors by the automated machine. Always ensure the mesh provides a flat enough surface for the specific dimensions of your die.

Q4: Do I need special equipment to unload dies from a vacuum release box?

A4: Yes, you cannot simply pull the dies off with tweezers effectively. You need a fixture or a machine stage that applies a vacuum to the underside of the tray. This vacuum pulls the membrane down through the mesh, breaking the surface tension. Attempting to remove dies without the applied vacuum can result in high stress and potential die cracking.

Q5: What is the shelf life of a vacuum release box?

A5: Most manufacturers guarantee a shelf life of 1 to 2 years, provided the boxes are stored in a cool, dry environment away from direct sunlight. Prolonged exposure to high temperatures or UV light can cure the gel further, altering its retention properties and potentially making it too sticky or causing it to lose tackiness entirely.